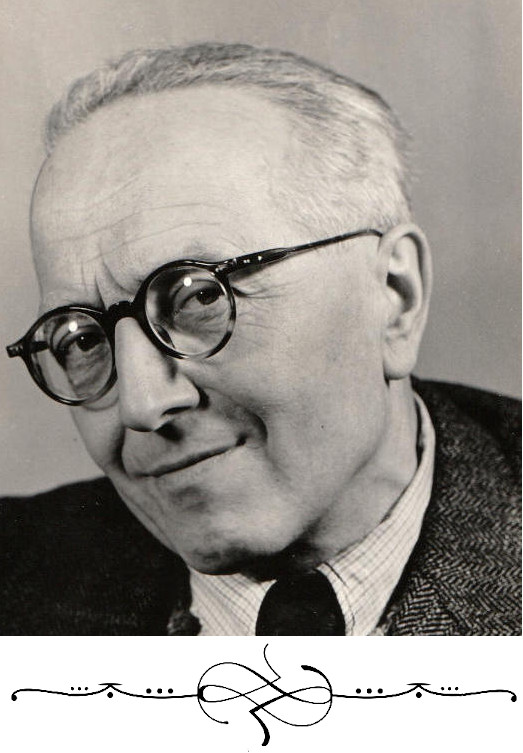

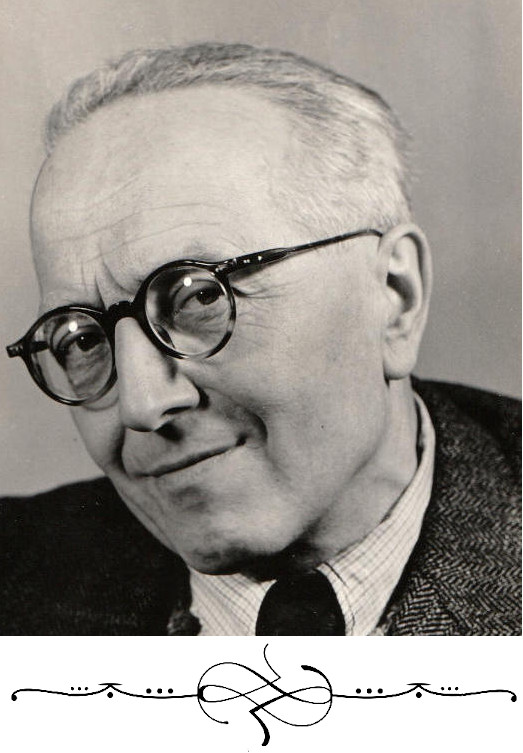

L A Ď A

JUDr Ladislav Vavruch, 1895-1967

Based on much longer manuscripts written in Czech by Mářa Vavruchová (1905-1994),

edited and translated by Petr Vavruch

Moravia

Laďa was born in Kroměříž on Wednesday the 26th of June 1895. He was baptised Ladislav František in the Church of the Virgin Mary (Riegrovo náměstí) on the 30th of June.

His father was a professor (high school teacher) Rudolf Wawruch (1852-1920) born in Kojetín, his mother Anna Vavruchová née Klapilová (1863-1944) was born in Lutopecny.

(

See photo of Rudolf and Anna)

Laďa's godparents were Rudolf's brother František Vavrouch, who had a small farm in

Kojetín, and his wife Johanna née Medková.

Laďa's grandfather Matěj, Rudolf and František are buried in Kojetín (in the middle of the cemetery on the main path, on the right) and Matěj's door sign and harmonica are in the depository of the local museum.

[Mářa's manuscript

Vavruchovi, the source for this chapter, includes 8 pages about Ondřej Ignác Wawruch, Beethoven's last doctor.

Click here for a very short version of his story.]

At the time of Laďa's birth, Rudolf's troubles were long gone and forgotten and his good work was highly appreciated, as was his 'analytical-direct' [?] method of teaching French and Czech, his favourite languages.

He also taught German and English. He was very conscientious. The schools he worked at in Ostrava and Kroměříž published a number of his essays and treatises in German and in French.

Ten years earlier, at a German-medium secondary real-school in Ostrava, other professors accused him of voicing biased nationalistic, anti-German, religious and anti-Semitic views during his classes.

We have only one silly example, there must have been more.

Rudolf criticised his student, Robert Wittek, for reading trashy books (

Nemáte nic lepšího na čtení?!) and said

Vítku, Sie sind auch schon tief gesunken. It was during a Czech lesson.

Rudolf made the mistake of sending, over the heads of his supervisors, a long, detailed report about the incident directly to Brno to the Central administration of schools in Moravia. The supervisors were upset, the affair was dragging on. In Brno, most of the officials were German-speaking liberals (while Rudolf was conservative) and it took a lot of effort by the Czech representative, Dr Fenderlík, to prevent Rudolf's dismissal. However, animosity from professors, some students and their parents lingered on. Rudolf protested and got this answer:

But you are a Czech! meaning that animosity could be expected.

There is no doubt that Rudolf was trying to instil in Czech students at the German school pride of being Czechs and prevent their germanisation.

For German-speaking professors and officials that was highly inappropriate. Of course, among Czech professors and many others, Rudolf became a hero.

He continued teaching at the school for five years and then the family moved to

Kroměříž – a historically important and very nice town in the fertile part of Moravia called Haná. Strangely enough, for Moravian speakers, the word Kroměříž is masculine.

Laďa attended k.u.k. (imperial and royal) Czech-medium government schools, starting on the 16th of September 1901.

His claim to fame as a little boy was to be caught spitting from their flat's

window on Jews walking on the pavement.

From 1906, Laďa was at the Czech 'gymnasium' (academic high school, grammar school) in Kroměříž.

One of his teachers was Mářa's beloved great uncle Pater František Schindler, brother of Mářa's grandmother Blandina Schwarzová.

Schindler had a problem with Laďa, who voiced his thought that the Earth was not created by God but everything arose from a bubble.

He might have been expelled if his father was not a teacher at the German real-school across the square.

Masarykovo náměstí in Kroměříž, major buildings from left: Laďa's gymnasium - Rudolf's reálka - church - Robert Jan's German school

Later in life, Laďa did not see any of his old classmates in Kroměříž as his friends, he did remember one whom he strongly disliked. That boy was snooty because his father was a high official in the Archbishop's administration.

As Rudolf's salary was only 6100 crowns per annum, and the family had three surviving children (Zdeněk, Lidka and Laďa) to look after, Laďa did not have to pay school fees.

However, the living standard of the family was good.

There was a maid, there was enough and good quality food, although a lot of it was sweet, e.g. baked rice pudding, milk pudding, bread and butter pudding, plum and various other sweet dumplings, stewed fruit for afters and 'koláče' for tea.

So that is what Laďa liked for the rest of his life while he did not like spicy food and salads. He was an abstinent.

Bábinka profesorová liked good coffee so fresh coffee was roasted every day.

Poultry and other foodstuff often came from Kojetín, Postoupky (half way between Kojetín and Kroměříž) and Lutopecny.

Their flat in the street Na valech was well furnished, every available surface was covered with crocheted or lace doilies and there was a big statue of

Karel Havlíček Borovský.

Rudolf had a big bookcase with a variety of books, several of them in French. The children also had many books.

Life was unhurried. Rudolf taught 22 hours per week; there were long evenings with a bit of music, talking or reading, Laďa liked that.

At home, the children learnt German and French. The holidays were long and the family always went somewhere, to Karlovice,

Jeseník or

Luhačovice... Then there was still enough time left to visit most relatives.

They were visited during the year as well, the whole family often walked to Postoupky or to Lutopecny (the same distance). Rudolf quite rightly considered walking and fresh air beneficial to health. He also encouraged his children to hold a stick behind their back for good posture. Many years later, Laďa did the same with Petr and perhaps with others as well.

In 1907 Rudolf travelled, as he had done quite a few times before that, to France, and his report, in German, was published by the school. He visited a number of places and met some colleagues. He also included his observations concerning some amazingly fine points of French grammar.

In 1908, Rudolf officially retired and the family moved to

Prostějov where Rudolf found new employment at a business college (Obchodní akademie). It was so good for him to be at a Czech school at last.

The family rented a flat in a large villa which belonged to JUDr Václav Perek, a well-placed lawyer, and his wife who was among the leading ladies in the town. It was all very friendly and pleasant. There was a nice garden.

Laďa's siblings were not always there. Zdeněk studied in Prague but also in Graz and Kraków, Lidka studied painting in the studio of

Alois Kalvoda. She met other painters: Roman Havelka, Kysela, Otakar Nejedlý... She was enjoying bohemian life.

Kalvoda organised a summer school in Bítov near Znojmo. A well-known composer, Vítězslav Novák (1870-1949), was also invited. He promptly fell in love with Lidka (who was already a leading beauty in both her home towns). When Lidka returned home, Novák visited Lidka, they dated, Lidka did not mind but the parents stopped it: he was too old. Novák then married Marie Prášková who strongly resembled Lidka.

In Prostějov, Laďa acquired good friends for life: Ladislav Roháček, Vlastimil and Otmar Šádek who had a group of music lovers where Laďa, who practised piano playing, fitted very well, Ivan Fleischer and his sister who later lived in Prague and always participated in their meetings. Then there was Laďa's admirer who was not his classmate, Pepek Vrba, with whom Laďa shared his life-long interest in photography.

But Laďa also started to travel alone, first to Prague, then to Šumava, in 1913 to the Alps. He took a lot of photographs. In 1914, he

matriculated in Prostějov.

In February the same year, Lidka married Vladimír Věrný (

see photo), an official at Průmyslová banka in Brno, later in Prague. They were married by Vladimír's brother Dorek (Theodor); his other brother was a colonel in the army. Vladimír came from Klenovice near Prostějov and was previously Rudolf's student at Obchodní akademie.

Lidka's parents considered Vladimír to be too young but the young people were too much in love to be stopped. Seeing that, Lidka's parents started to help. It was needed because the bank did not want to allow the marriage, Vladimír's salary was less than 3000 crowns p.a. They required a surety of 46 000. Rudolf offered 25 000. We don't know why Vladimír's father did not help. He was rich and liked to show it, so he organised a grand wedding in Klenovice. We also don't know what exactly happened in the end except that there was a new bond of 24 000 registered on the farm in Lutopecny No. 41.

The high society in Kroměříž consisted of a number of families, above all the Sixts. The sister of Mrs Sixt married Mr Hudec. Unlike Mrs Sixt, the Hudecs did not care too much about their social status. After Mr Sixt, who was the chairman of the board at a sugar factory, died, most of the family moved to Prague.

The Hudecs lived in Bubenečská ulice in Dejvice, near Sokol. They had two daughters whose best friend was Eliška Kořánová, daughter of Robert Jan Kořán and his wife Marie.

(

The Kořán family in 1914) The Hudecs sometimes invited other young people and thus Eliška met Zdeněk Vavruch. It was just before WWI.

Nine year old Mářa, Eliška's sister, was horrified: the Hudecs were Protestants! Eliška had to assure Mářa that the Hudecs were, but the

Vavruchs were not.

War

Soon after that the war started,

Laďa was drafted as a 'one-year volunteer' – a scheme for matriculated men to serve only one year but without pay until they became officers; they also had to buy their own gear.

He was allocated to the medical corps and trained in the Alps, Villach, Sankt Veit an der Glan, Ossiacher See, Budapest and Znojmo. (

Laďa when he was in the Alps)

He was reading a lot, but otherwise he was frustrated by the enormous waste of time. The way the others spent their time did not appeal to him.

Both Vladimír and Zdeněk were also drafted. Vladimír was lucky, most of the war his unit was in Šumava and Lidka could join him there.

Zdeněk, accompanied by a good orderly, was fighting in the mountains near Mostar in Herzegovina and Kojnic in Bosnia.

He experienced the worst of the war including the hanging of

locals accused of helping the enemy.

To keep him sane, he had a doberman,

Gizil von Sappen, who became the subject of lively correspondence between Zdeněk and Mářa.

Of course, Eliška wrote to Zdeněk even more.

At the beginning of May 1916,

Laďa was sent to the front in Volhynia.

Here, in the opinion of the German High Command (General Hans von Seeckt), Austrians were conducting the war with infuriating sloppiness (Schlamperei).

In his postcards, Laďa mentioned Koveľ, Manevychi, Kolky and Arsenovychi.

On the 20th of June 1916, during the Russian

Brusilov offensive that cost the lives of well over half a million soldiers,

the Austrians started an attack on Hruzyatyn and half an hour later Laďa was wounded.

For him that was that, he would not participate in the war any more. He was not even 21!

The problem was that his injury was slight, a clean shot right through his upper thigh.

It felt like being hit with a hammer but there was no real damage, no infection, he could be back on the front in a week or two.

It required some creative thinking and a very strong will. He

claimed that the leg was permanently bent and could not be straightened.

The doctors did not believe him, they used

some gadgets. They took him to the hospital in Chelm, then in Vienna.

They tried to anaesthetize him by using ether but he was trained by the medical corps so he knew what to do. He pretended he was breathing but held his breath. At the right moment he pretended to be asleep. They pulled his leg, he was holding it. They gave up.

During those uncertain times, the Vavruchs invited Eliška and her parents to visit them in Prostějov, spend a few days and meet Lidka who happened to be there. Mářa went as well.

On the train, Robert Jan was wondering if it was a good idea. Shouldn't they turn back? The Vavruchs knew that Laďa was on the front but not much more. What if they received some bad news? In that case, the Kořáns would show their support and go straight back home. When they arrived, the Vavruchs were smiling: Laďa was wounded but it was not at all serious. On that train to Prostějov, Mářa learnt that there was also a younger Vavruch.

Mářa liked the Vavruchs and

their flat, everything was so nice and pleasant. Lidka was hospitable, sweet and sisterly and lent Eliška one of her dressing gowns. The Kořáns did not have dressing gowns, it was too much of an indulgence. But Lidka, wisely understanding, also played a lot with Mářa – they sewed dresses for dolls.

In Vienna, Laďa rented a big room in Schikanedergasse with a view of the trees. He practised piano playing, enrolled in the law faculty at the university, went to concerts and theatres, to outings around Vienna and in winter he skated on one leg. He also liked to visit a certain nice lady whose identity got lost in time. He had some army duties but we don't know anything about it.

It was a good idea to avoid fighting! Mářa's brother

Vikin was fighting on the Italian front. It was the only front where the Austrians, fighting a numerically superior enemy, could claim real success. The fighting was so heavy that Vikin's hair turned white.

Czechs fought in WWI on both sides. About 100 000 Czechs and Slovaks fought the Central Powers in Russia, France and Italy.

Some of Laďa's cousins, Vavrouchs, were among them.

But many more Czechs (1.4 million) did not have the opportunity, stayed in the Austrian army and fought for the Monarchy, some of them with great bravery.

About 240 thousand were killed or missing in action.

On Friday the 18th of January 1918, Laďa went with the rest of the family to Prague.

In Hotel Paříž, they met the Kořáns and thus Laďa and Mářa met, at 7pm, for the first time. Mářa was 12.

The next day, Mářa's sister Eliška married Laďa's brother Zdeněk in the St Wenceslas Chapel of St Vitus Cathedral and Laďa returned to Vienna.

It is not clear why the Kořáns had misgivings about the marriage. It took a lot of correspondence, torment and tears before they approved it. Was it perhaps because Zdeněk was returning to the front and could be killed the next day? First, Eliška and Zdeněk had to be engaged.

To do that, Zdeněk was granted a short leave from the war and arrived in Cerekvice on the 15th of August 1917 with his parents and his highly pedigreed dog.

Early in summer 1918, the Kořáns went to the Alps. On their way, they visited Laďa, Rudolf was also there. They all went to Schönbrunn and the zoo. Mářa wrote in her diary: Vienna, Schönbrunn, Vavruchs, animals.

Czechoslovakia, born on the 28th of October 1918, established a military office in Vienna that,

on the 9th of November 1918, issued a certificate written in Czech allowing First Lieutenant Ladislav Vavruch to return to Czechoslovakia.

His leg was now straight, but weakened. He walked with a stick. He did not like to talk about it, so we do not know how much he exercised his leg in Vienna.

Perhaps he did not want to make it too healthy.

Prague

Laďa's Viennese student record book was used in Prague to complete the semester at Česká universita Karlova Ferdinandova.

He moved to the Kořáns' Vila at U Písecké brány 24 and joined the Vavruchs (Zdeněk and Eliška) for meals.

Occasionally, the Vavruchs or sometimes Rudolf alone came to Prague. At that time, cultural contacts with the French were frequent and popular.

Mářa followed it and took Rudolf to such events.

Rudolf enjoyed listening to French speakers and, when there were none available, Mářa recited to him French poems that she learnt from Mlle Josephine Heyer who came to Vila.

No wonder that Rudolf wrote to somebody that it would be nice if Ladíček also married the Kořáns’ daughter – that Mařenka. Before they themselves thought about it.

The family did not attend Laďa's graduation (

see the notice) on the 17th of July 1920. The Vavruchs no longer travelled.

Rudolf had heart problems and worsening sclerosis while Bábinka profesorová had very high blood pressure.

She also did not see too well so she always appreciated it when somebody was reading to her. Later she developed diabetes.

After the ceremony, Laďa immediately packed up and travelled to the High Tatras to join the Kořáns in Štrbské Pleso.

To save money, he walked uphill from the railway station in Štrba in a terrible storm. The Kořáns worried about him. Anyway, he now felt accepted by the Kořáns.

The following year, the family went to the Alps. That was Robert Jan, his wife Marie, Vikin, Mářa

and Laďa.

When Laďa visited his parents in Prostějov, he met his friends and some comrades. There was a big, well-known high-quality garment firm in Prostějov, with a lot of workers and very active socialist agitators, including future Minister Rudolf Bechyně (1881-1948). Laďa's social feeling originated there.

He became a member of the Social Democratic Party on the 1st March 1919.

He talked about human rights at a big meeting and contributed articles to the local SocDem newspaper

Hlas lidu (The voice of people) starting with

Why I am a socialist on the 7th of September 1920. This was followed during the next two years by at least eight articles covering various economic issues. From 1924 to 1926, Laďa wrote articles about the sugar industry published in the SocDem national newspaper

Právo lidu (The people's right) and in 1926 and 1928 also in

Prager Tagblatt and

Tribuna.

In Prague, Laďa started working at the Ministry of Commerce that had offices in Valdštejnský palác.

Laďa's work was very pleasant. His boss, a fellow Moravian, JUDr Josef Benda, was kind and the colleagues were friendly. Laďa was their photographer and they all visited each other. That continued even after Laďa stopped working there. Office hours were short. He had a reasonable salary of about 8000 crowns p.a. and it was increasing as he passed, always with excellent results, various internal exams, and as he was given more responsibility. He also became a member of the external Advisory commission for economic affairs. He published articles in professional economic periodicals and wrote a number of extensive internal reports and recommendations.

In his free time he read, played the piano, studied philosophy...and spent time

with Mářa. At first in secret, with some help from Vikin, later it was allowed. They walked the old streets of Prague, spent a lot of time in Hradčany, went along the river and across the bridges, to the parks, to Šárka... and, which was their favourite, climbed up all available towers in Prague.

It was initiated by Mářa. She went from Klárov by tram and saw Laďa walking slowly uphill with a stick. When the tram slowed down at the bend, she jumped out to be well ahead of Laďa on the pavement.

Would he catch up with her? He did.

Rudolf wrote that he would like to see Zdeněček, Elišečka and Ivušek.

Ivan (later Ivoušek,

see photo of Ivan when he was 19) was the first child in the next generation, born on the 19th of November 1919.

Rudolf also wrote that Zdeněk should not hesitate to ask Robert Jan for help when he was organising his law office.

He stressed Robert Jan's resourcefulness, ingenuity and entrepreneurial spirit. (

Click here for Robert Jan's early life)

So, on the 31st December 1920, Zdeněk travelled, alone, to Prostějov. He was looking forward to telling his parents about his work. At the station, he was met by someone but the man did not tell him that Rudolf was already dead. Zdeněk walked in, saw his father and passed out. After Rudolf's death, Bábinka profesorová closed the household in Prostějov and moved to Prague. At first she shared the room with Laďa in Vila.

Rudolf overexerted himself. After the war, there was still a shortage of food, and supplies were strictly regulated. Nobody was supposed to have more than their basic needs. The Vavruchs had more – they had an extra bag of flour from the farm hidden in the attic. Rudolf went to fetch it, it was too heavy for him to carry all the way, his heart stopped. He was 68.

In the middle of 1922, Mářa finished her 6 years at 'girls higher' school.

As she was to go to Dresden to a private 'finishing' school, the whole extended family (including Blandina, Anna, Zdeněk, Laďa, Eliška and little Ivan) went holidaying to the German island Juist to improve Mářa's German. Not to miss anything, Laďa made a quick detour to Helgoland.

Previously, Mářa had looked forward to Dresden, she had loved her sister Eliška's room in Töchterheim Römer, Leubnitzerstraße 19, ten years earlier. But now there was Laďa!

Laďa was not thrilled either. He declared that rather than be in Prague without Mářa, he would go to Paris. He applied for a bursary granted by the Ministry of Education using French funds, 6000 francs plus train tickets. Signed by the Minister of Commerce, the ministry allowed him ten months of unpaid leave.

During their train journey to Dresden, Mářa asked her mother two important things.

Firstly, not to call her Maritsch when speaking in German.

It must always be Mářa in both languages and the Germans can mangle it as they wish.

Secondly, her mother should ask the headmistress to allow Mářa to go for a walk with her fiancé when he comes to visit her – and that they will also frequently write to each other. It was a white lie so it needed some determined persuading. In the end her mother agreed.

Mářa and Laďa were not engaged. It was taken for granted that they belonged together, no engagement felt needed.

During their many walks and letters, Laďa was moulding the

ten years younger Mářa to create a perfect wife for himself.

It does not look like he fully appreciated how strong a personality Mářa was. Later in life he realised that, perhaps, he was wrong.

In his manuscript

Takový je život

(Life is like that) written in 1958, he wrote:

You think, driven by your ideas created on the basis of your experience, that you lead her to your ideals. You don't see, next to you, a being with her own particularity, her own vitality drawn from her instincts filled with the energy of her youth. Nobody can adopt outcomes of somebody else's experience...it is ambience that stifles the young person's independent aspiration and it drags even into an embrace a worry that there is something else, not fully understood, stopping her from trusting herself and her enjoyment.

When Laďa was in Paris, they exchanged 140 letters, full of love and tenderness. They wrote in great detail about what they were doing but also about their future life together, often on his part quite obsessively. To achieve the best, nicest, fullest, most harmonious life without any imperfections required, of course, a lot of well-meaning instructions for Mářa. When he put it too strongly, Laďa felt miserable about it and profusely apologised.

He also worried that Mářa might be unhappy because their standard of living would be lower than that of their siblings – Zdeněk's law firm was very lucrative. All their letters were made secure by melted bright red seal wax pressed down with metal stamps.

With all those letters and school work, life in Dresden was exhausting for Mářa but she also enjoyed herself: Germany was cheap for Czechs at that time.

Mářa did not bring much stuff with her, she bought everything that she needed in Dresden.

She was also buying decorative items, the best chocolates Drei Mohren and Sarotti and...luxury writing paper costing only 20 000 marks.

Laďa arrived in Dresden on the feast of St Wenceslas, the 28th of September 1922. They were allowed a 2-hour walk.

It was hard to say goodbye. On the 7th of October, Laďa travelled from Prague to Paris. He was 27.

France

In Paris, he studied at École libre des sciences politiques, wrote articles, visited factories (e.g. Renault), the International Chamber of Commerce, Louvre, museums, churches and L’Institut d’études slaves (which supervised his studies). He admired architecture in Paris, particularly the Gothic churches. He was also learning English. He did not waste time and he loved it.

Often he sat reading, studying and writing in the Luxembourg Gardens. He lived frugally to save money for theatres, concerts and travels.

Too frugally. After a few months he had jaundice and cheap cooking oil was making him sick. The only cheese that he could eat was the very mild Petit Suisse Gervais. He spent money in a confectionery only once, in Marseille, to celebrate that he was feeling happy.

He did not eat other cheeses also for another reason: he had developed a strong dislike for cheese. That is because when he was in army training in the Alps, the soldiers were fed Emmentaler and hardly anything else.

There were other Czechs in Paris and Laďa met some of them.

Are you that Vavruch from the Kořáns?, Honza Květ asked him. Květ dated Boženka Matějovská, previously a friend of Mářa mainly because Boženka lived across the fence from Vila.

Květ and Laďa became great companions and Květ persuaded Laďa to go with him to Prague for Christmas. Just for a few days. Laďa was concerned that the Kořáns would see it as a break of the "trial separation" but he did not have to worry, everybody liked to see him. Květ was not so lucky, Boženka no longer wanted him but he did not get a straight answer from her.

For the trip, Laďa needed to dip into his savings, the bursary did not cover a mid-term trip. And he bought Mářa an ivory brooch with amethyst.

Mářa was in Prague early to attend Vikin's graduation on the 13th of December 1922. It was the first graduation ceremony of the newly independent Faculty of Natural Sciences at Charles University. So Vikin was among the very first RNDr.

On their way back to Paris, Květ and Laďa did a lot of sightseeing in Nuremberg, Würzburg, Frankfurt, Worms, Heidelberg and Strasbourg.

For the Easter visit of the Kořáns in Paris, Laďa prepared a detailed plan. They arrived on the 29th of March 1923; Vikin and

Olu (scroll down on that page) came from London. Vikin worked in London with Prof. Druce and stayed in his house. Olu enjoyed her stay in a boutique hotel.

Laďa thought that the student-accommodation type Hôtel Saint Sulpice, 7, rue Gasimir Delavigne, Paris VIe where he lived was good enough for the Kořáns and it was, except for Olu. She did not unpack and moved to hotel Odéon.

Springtime Paris was beautiful, lovely tulips everywhere. They walked to all important sights, Olu complaining that a taxi would be better. Laďa and Mářa did not worry about her, they spent a wonderful 16 days together.

On the 19th of April 1923, Laďa left Paris, visited Lyon, Avignon, Arles and other places and arrived in Marseilles on the 24th. He stayed there until the 4th of June, signing up for a course at Institute colonial. Armed with a letter from the Czechoslovak consulate, he visited the harbour, industrial and commercial enterprises... and in his spare time Nimes and Aigues-Mortes to the west and Nice and Monte Carlo to the east.

Then he went to Tunisia. The sea was rough, the swell more than 3 metres, he was just unable to take the supper served to the 3rd class passengers in the fore of the ship. It was torture, everything was jumping around and he was quite sick. The food, some meat and bread, was not appealing anyway. He went to the deck in the middle of the ship and spent both nights on a deckchair, ignoring his bed in the sleeping quarters. When the storm died out, he saw the rough coast of Sardinia.

Africa! There was so much to see and it was so exotic. Trees and flowers in amazing colours and fragrance that he had not seen before. He wrote:

Everything that is beautiful is here. But Laďa also noticed the contrast between the city and the countryside. Tunis was European and young people of both sexes dressed that way, women walked in the streets wearing trousers and white shawls, heads not covered. Men still had traditional white robes that contrasted with their dark skin...and bracelets.

He was excited about Kairouan, an important centre for Sunni Islamic scholarship, where he went by train:

A fairytale about a desert and Arabic life...like in Arabian Nights. But Laďa was shocked by the ordeal of Arab women there, far from Tunis. They had to stay indoors and work the whole day while men went shopping and then relaxed. They did not move much and Laďa noticed that they were pot-bellied, their hands were soft, their arms without muscles, their legs thin like sticks. There were no women in the streets.

Unmarried men also worked. On the ship, Laďa spoke to a black man from Congo who lived in Tunisia. He told him that he already bought two women, 2 thousand francs each. Now he would buy a third one and that would be enough, he could stop working. Another man, from Algeria,

did not have a high regard for Tunisians; according to him, they were backward and uneducated.

Laďa thought about it. What was the alternative? The Arabs who were not rich to start with and did not have any useful education or training to prosper in European society, could only be low-paid badly-exploited labourers. Social issues always concerned Laďa. He was a Socialist but it was mainly intellectual and he did not feel the need to rub shoulders with fellow comrades. So he probably did not involve himself politically in France.

Laďa did not like how rich Arabs treated other people, how they spit in public and most of all how cruelly they abused animals. And while the Arabs appeared friendly, he was pleased to have his revolver. The ability of young men and women to be amazingly swift made him nervous.

Back to Tunis and then by bus to Téboursouk in the middle of the mountains. It took 5 hours to get there but it was scenic all the way. To visit the Roman ruins in Dougga, a Berber, Punic and then Roman settlement of the 3rd century. He had to walk 12 km to get there and then walk back in heavy rain without a raincoat. After seeing the great structures, rows of columns, theatre, mosaics... he was impressed:

Our homes are miserable eggshells in comparison with these buildings made to last centuries.

In the morning he returned to Tunis, bought some food and a ticket and went aboard. This time

it was a 4th class ticket – no bed, no food. He did not miss either and enjoyed the thought that the deck where he stayed was where the 1st class passengers had their cabins, too.

Laďa travelled to Paris via Dijon and some other places. It took him four days. He finished his studies and selected the

scenic route (see also Kitzbühel) by train to Prague via Innsbruck. He still had three weeks before he started working again on the 10th of August 1923.

During those 10 months in France, he often realised that he lived and acted to the very limits of his stamina and how he lived in constant restlessness trying always to achieve the maximum.

Wedding

Laďa got his job back and was good at it, his proposals were accepted, his work was appreciated; he liked it because it was creative.

In his spare time he was with Mářa but also with her parents, going to concerts, theatre and outings. The first winter they all went to Luční bouda in Špindlerův Mlýn to ski.

When Mářa was in Cerekvice, Laďa went there for the weekend. In Prague, they spent a lot of time at Eliška's piano, not only to play and sing but also to talk about art, philosophy and life.

Mářa and Olu were learning to cook and Laďa's main concern was to find a suitable flat. It was next to impossible. The ministry would financially support him if he built a standard model house in Ořechovka, maybe the Kořáns would chip in, too. But Robert Jan did not like those houses. They were too small and not the same quality as Vila, which of course was hard to match.

Robert Jan had a better idea. He consulted his business associates, organised a few swaps of flats, sweetened the deal by buying four nice pictures painted by Josef Fiala [one is in our sitting room] and thus made it possible to buy two identical flats next to each other in Bráfova ulice Nos. 8 and 10 (now ulice Československé armády) from the supplier of coal to Cerekvice, Mr Kleinhempl. One for Vikin and Olu and one for Mářa and Laďa.

Furniture for the new flat and handmade carpets were based on the designs of the architect of Vila, Ladislav Skřivánek, and made by Kallik Co. After they moved in, there was also a good maid who slept in a little room with a window to the staircase. And a huge ginger cat whom they found abandoned in the street as a tiny kitten. Bedroom windows faced into the yard between the blocks of flats where there was a double-storey garage with a lift. A piano and a full set of linen was a gift from the Kořáns. Some of the decorations, batiks and wall hangings were made by Mářa herself in an evening course at an art school. Wall paint colours were professionally selected.

Robert Jan was good at organising things. Mářa particularly admired how he managed to find a bride for Rudolf Kiezsler, the key man in the plant in Cerekvice whom Robert Jan brought from Moravia.

Mářa and Laďa got married by Mářa's uncle Pater František Schindler (Laďa's nemesis in Kroměříž) in

St Wenceslas chapel of St Vitus cathedral on Saturday the 12th of April 1924 (nice date 12/4/24). At the reception at Hotel Palace in Jindřišská ulice, Zdeněk announced that their daughter will be named Alena because it was Mářa's wish [?].

The newly-weds collected their luggage and went by train to Trieste, Venice, Padua, Bologna, Florence, Pisa and Corsica where they ran out of Laďa's annual leave so they had to return home. As a souvenir, they bought a huge ceremonial knife with an inscription

Che la mia ferita sia mortale, Vendetta Corsa.

Vikin and Olu married on the 14th of May 1924 and Olu joined Vikin in his big southern room on the 2nd floor of Vila until their flat was ready, while Mářa and Laďa used the

north-facing (cold) room. Laďa's salary was not quite sufficient to support a family. So after they got married, the Kořáns provided most of Mářa's wardrobe plus 500 crowns per month.

Laďa had a law faculty degree JUDr but never wanted to be a layer. In Czechoslovakia, JUDr was considered to be a general purpose degree, Pavel had one, too. Nevertheless, Zdeněk persuaded him to register in his office as an articled clerk to give him more options in the future.

Cerekvice

(

Click here for the factory's early history, scroll down on that page)

(

in Czech)

Again, Robert Jan had a better idea: Laďa could join him in Cerekvice and his salary would be higher there.

Laďa's boss JUDr Benda agreed with the decision and wished him well. He had already said earlier that Laďa was too good for the Ministry.

Now Laďa had to learn accounting. For that Robert Jan hired a tutor who came to Vila.

At the same time, Vikin also started working in Cerekvice. For him it was more painful, he wanted to be a scientist and work with professors Druce and Heyrovský. In the end, he became a top expert on all aspects of the sugar industry.

And thus started commuting by train, 150 km, twice a week. It lasted 24 years. For Laďa, Cerekvice was never his home and not a nice place for holidays either.

He just worked there.

And it must have been frustrating. The enterprise did not accumulate any capital, there was no capital, it was all loans from the banks.

What was earned went back to the banks in the form of interest. Yes, it ensured a modestly comfortable life for the family.

Too comfortable as far as Herr Hoffmann was concerned. When Robert Jan worked in Moravia, the major banks were in Vienna. The general manager of Länderbank, Emil Freund, took a liking of Robert Jan and supported him. After Czechoslovakia was created, Länderbank had its offices in a big palace near Obecní dům in Prague. Mr Hoffmann was in charge there. He had instructions to treat the Kořáns favourably but he did not see why he should make it pleasant. There were long negotiations, sometimes followed by Hoffmann's telephone calls to Laďa in the evening. There was no advantage for Robert Jan to negotiate with Hoffmann, so it was done, probably in German, by Laďa and Vikin. Only gradually, long after the negotiations, did Hoffmann become more friendly towards Laďa.

Hoffmann was holding all the trumps so the result of the negotiations was unfavourable. It would be, of course, out of character for Robert Jan, Vikin or Laďa to complain about Hoffmann in Vienna and nobody could imagine that just 10 years later, banks would compete to have the factory's business. It was a collective achievement but, on the financial side, it was to a great degree due to Laďa's efforts.

There were other banks that were used as well, particularly Pražská úvěrní banka.

In

Cerekvice, Robert Jan and Vikin were enjoying themselves: they mechanised, modernised, upgraded, improved, invented and tried new things.

It cost a lot. Sure, the production boosted and the top quality was achieved.

Sugar lumps were available in a number of shapes and sizes, as well as various types of crystal sugar and icing sugar.

It was exported under the trademark

CRC (Cukrovar a rafinerie, Cerekvice) decorated by a cross, shipped in a variety of packages from small to very big. Granulated fines and lumps were exported to England, special extra small cubes in fancy boxes to Akkra in Africa, natural colour white sugar to Nestlé in Switzerland, etc.

When the factory was nationalised in 1948, Vikin was pleased with himself:

We are handing over a well-built factory.

Laďa followed the technical developments with genuine interest while he was trying to keep the ship financially afloat.

He kept a tight ship in accounting and administration. All of it in a friendly demeanour. Just like Robert Jan and Vikin, he made sure that employees were happy.

At least once a week, he went to the plant, not to spy on people but to show interest and appreciation for their work.

He made sure that he shook hands with all permanent employees and at least said

Hello to everybody there.

People knew that their collective effort made the enterprise successful and they were proud of it. They called Robert Jan 'Pan šéf' (Mr Boss) and Vikin and Laďa 'Pan doktor'.

After visiting the plant, Laďa went back to his painstaking effort to ensure that everything was done the best possible way.

The factory produced sugar during ‘kampaň’ (the campaign, or season) that started when sugar beet became available in September and lasted 4 or 5 months.

The permanent skeleton

staff was supplemented by many seasonal workers.

The campaign could be extended by refining raw sugar purchased from other factories, some of them far from Cerekvice.

It could then run to February or April but working the whole year was never achieved. When during WWII the 'dry' campaign was once extended to June, it created a problem: both the machinery and personnel were overheating.

Logistics were paramount and that was mainly Laďa's and his staff's responsibility.

For instance, the timing of railway wagons arriving with sugar beet and coal because they should not be waiting in a queue.

They were emptied as fast as possible and filled with what was left from the beet after it was cut into chips and the sugar extracted.

These 'řízky' were sent back to the farmers to use as fodder. The wagons were pulled, first by oxen, later by a locomotive, from the factory siding to the railway station where they became the responsibility of the railways.

Any delays in holding the wagons were very costly.

In the last years before WWII, big lorries were also used because they were more flexible.

Another important task was to prevent any disputes by supervising weighbridges where the sugar beet was loaded on the wagons.

Laďa kept detailed records of sugar prices and the prices of construction materials and engineering supplies, coal, coke, limestone, packages, sugar beet seeds and various other commodities; as well as of sugar consumption, production and demand in several countries.

In his notebooks, he recorded daily statistics of all phases of production in 17 columns and its monetary significance.

Some of the items were sugar beet delivery, sugar beet utilised, sugar content, sugar produced: (a) raw, (b) refined, which kind, sugar sent out, consumption of coal, packages used, etc. He calculated the cost of production in individual sections of the plant including wages and materials.

Apparently, this micromanagement was important and Vikin also had detailed knowledge of the cost of production and other statistics.

Laďa's knowledge of markets and trends allowed him to negotiate the best deals both in sales and purchases. Laďa was a tough negotiator, but I am sure that he was fair.

He just used his superior knowledge. Perhaps some did call him a "horse trader"; I would see it as a compliment although it does not sound too nice in Czech (koňský handlíř).

When a premium price was possible for an urgent delivery, Laďa discussed it with Vikin to decide if that kind of sugar could be made in time.

Laďa also negotiated with the farmers, agreeing with them on the planting area (measured in hectares). The factory supplied them with seeds.

The price of sugar beet was fixed in Czechoslovakia, but the farmers could get a bonus for supply above the contracted tonnage. Without happy farmers the factory would not survive.

As a secretary, Laďa ran the Association of sugar factories in the Pardubice region (Sdružení pardubických cukrovarů) founded and permanently chaired by Robert Jan. There were 14 factories, later only 11. One of those that had to close down was decommissioned by Laďa. He started working on it in 1929 and it was hectic. He could not even take his leave that year. He always worked too hard - to the point of exhaustion.

This oldest sugar factory in the region (1868) was situated in Vysoké Mýto, the closest town to Cerekvice.

It produced raw sugar refined in Cerekvice and was effectively owned by Robert Jan who gradually bought most shares.

It came to its end when the economy was in crisis and all the sugar factories were struggling.

The small plant was obsolete and in bad shape and would require a major reconstruction. Fortunately there were not many employees who needed assistance.

All routine HR tasks were always done by Laďa.

[Perhaps Robert Jan was looking forward to the pleasure of rebuilding yet another sugar factory.]

The association worked extremely well. There was no point in fighting, poaching farmers or hoarding supplies. It was much better to agree on things and help each other with logistics, spare parts, commodities and personnel. Sugar beet producers were firmly allocated to various factories. In Robert Jan's case it was not too complicated because Cerekvice was at the edge of the sugar beet growing area. Beyond that, the main crop was flax. The association dealt with central organs and organised the joint ordering of sugar beet seeds and raw sugar.

For the relevant authorities, Laďa wrote extensively about these practices and the industry as a whole, analysed the situation and made proposals to institutions. He even drafted texts of two new laws, one about the management of sugar factories and the other more general about support for enterprises involved in export. The proposals were not accepted.

The crisis continued and Cerekvice was also in danger. Rich capitalists were looking for opportunities, they could pressurise banks and take over the factory quite cheaply. So in 1932 the status of the factory was changed from a private enterprise to a limited company with sugar beet producers getting some shares. That made the factory safer. Although this project was well within Laďa's skills, we don't know how he was involved.

More institutions and organisations regularly visited by Robert Jan and later by Vikin and Laďa were in Prague: banks of course, insurance companies, the sugar industry central office (where they represented their association), the sugar factories cartel, the central office of sugar beet producers, the society of sugar beet seed producers, sugar, coal and other wholesalers, even trade unions.

Private life, part one

Mářa writes that Laďa's private life was complicated, multilayered. I believe that hers was much more complicated but there is not a word about it in her writings.

Mářa does not let the juicy complications out but they are confirmed in Laďa's own

Takový je život.

[Very intriguing, and for me sometimes confusing, text, 9 pages, unfortunately beyond my ability to translate. It starts with an apparent justification for Laďa's political beliefs.

This justification was badly needed after experiencing the worst years of the communist terror.

We don't know if it was the same justification as the one he gave in his article 'Why I am a socialist' published in September 1920.

This one reminds me of a quote from François Villon (1432-1467)

Necessité fait gens méprendre, et faim saillir le loup du bois.

It was Laďa's concern about uncontrolled violence and destruction by the downtrodden.

Laďa did not read much poetry thus, if it was his inspiration, he might have got it second hand from Jiří Voskovec's

...že bída z lidí lotry činí, že vlky z lesů žene hlad

in the song

'Hej pane králi'. The song was in the play 'Balada z hadrů' (1935) about François Villon.

Laďa liked to go to

Osvobozené divadlo to see plays by V+W, and Voskovec knew French poetry well.

Laďa, always an optimist, believed that the communist regime would be able to solve the problem. In a way, he was right.

While we were poorer than our neighbours in capitalist countries, it was bearable, nobody was hungry, nobody was allowed to be unemployed, and any uncontrolled violence and destruction would be brutally suppressed.

There is not much about Laďa's life in the text, besides Mářa and Jarmila, without naming them.

No other specific joys and sorrows, not even dancing, his music or his writings. No friends, no relatives besides Mářa and nameless children and grandchildren who merely serve to show how the time flies. Not a word about his work, only as a source of income. Just scattered philosophical reflections of life.

In his text, Laďa identified Mářa as the girl to whom he gave a red rose. At first I thought that it was poetic and whimsical and maybe it was.

But there was a real red rose. Laďa first kissed Mářa on the 13th of October 1920, and the next time he saw her he gave her a beautiful red rose.]

Mářa attributes the complexities of Laďa's life to the complexity to Laďa's character – his profound personality, serious thoughtfulness, richness of mind, sensitive understanding and straight sincerity. When he could not avoid conflict or an unpleasant experience, he had the ability to rise above the situation and appraise it 'from above'. He enjoyed formulating thoughts and would have liked to devote himself to doing that. He managed quite a lot of it: there were many articles, long and short, printed essays...and much more left in manuscripts.

By his standards, Laďa's private life must have appeared to him as an unmitigated failure. Except for short periods, he did not get what he wanted and what he described in his 80 letters from Paris. He wanted a life filled with music, art, literature and philosophy, if not the whole day then at least during long evenings. It did not happen, there was no time for it. When he worked in Cerekvice, it was exhausting work, Sundays too short to recover, then at last a holiday.

But it was

not all bad.

When Laďa was in Prague, they went to concerts, to opera (Mářa's favourite), to Mr Garlick who combined English classes with his supper, to ballroom dance courses in Lucerna, and so on.

Then there was social life, they regularly met their friends. Laďa's friendship with Honza Květ (later Akademik Prof. PhDr Jan Květ, 1896-1965) morphed into Mářa's life-long friendship with his wife, Eva, a pianist.

Beyond that,

the Květs introduced the Vavruchs to their numerous friends. The Vavruchs also went out frequently with Vikin and Olu.

The first holiday, in 1925, was an adventure. Vikin thought that Laďa should buy a car, so he did, a second hand Renault, two-seater. They reached Sereď in Slovakia where uncle Jindříšek worked, it was a pleasant visit. They drove on but then the car gave up. It was Laďa's fault. They got stuck in the mud and he was feverishly shifting gears between the first and reverse until the gear lever came off.

The car was kept in a garage near the river Lubochňanka. The river flooded with the water reaching to the car seats. Mářa mentioned that they watched it across the river. [I wonder if she swam across a couple of times, it would be well within her character.] The car was pulled out and repaired. However, Laďa was tired of constant valve adjustments and sold it in Valašské Meziříčí to a vet who apparently used it for a few more years. Laďa and Mářa returned to Cerekvice by train. Not too glorious.

Then there was a tragedy. In November 1925, Pater Schindler, on his way home from the Castle, was hit by a car and died.

Laďa was a keen photographer. He developed films and printed photographs himself (in the bathroom), trying various techniques. To catch the life of the new little one who was coming on film right from the beginning, Laďa bought a huge wooden camera on a stand, using the full size 32 mm film. Later he exchanged the cameras for smaller ones and used the smaller format 16 mm. He did not go for 8 mm. For photographs, he also changed cameras, having good knowledge of lenses and mechanisms. He particularly liked Leica [just like Shani's Pa] but during Protektorat he had to swap it for food.

I do not know how he incorporated children into his ideal of a highly intellectually-charged, harmonious marriage, the answer is perhaps in the

Västerås municipal archives where Pavel deposited Mářa’s papers as well as his own.

There were two boys.

Alešek was born on Saturday the 8th of May 1926. He was a victim of the 'modern' method of bringing up children, basically tough love. If a child cries, move him to another room so that he does not disturb you.

But he had a nice pram, dark blue, spacey, selected by Robert Jan to compete with the Heidlers who were also promenading in the vicinity with their baby.

At first, little Alešek spent most of the time in a pram, inside and outside. In Cerekvice, it was a white one inherited from Alena.

A crib or a basket were considered an unnecessary luxury – a baby would soon grow out of it.

The fancy blue pram was heavy and needed to be carried upstairs and downstairs, or dragged or dropped step by step.

When it got into the flat, the wheels were wiped clean and Alešek stayed in it. In autumn, Alešek got an expensive golden-coloured 'Paradies-Bett'.

In June 1927, Laďa went to Kopřivnice with the name of a foreman at the car factory. The foreman was chuffed and selected for Laďa the best specimen of Tatra 12 available there.

The car had a

canvas roof and one door.

It was immediately put to use, the family went to Karlova Studánka in the Hrubý Jeseník mountain range for the holidays.

The next year the family went on holiday early because Mářa was pregnant again. (

Photos of Laďa and Mářa in 1928)

In May, they took Bábinka profesorová to the island of Rab in Croatia. She liked the southern seas.

Pavlíček was born on Sunday the 9th of September 1928. Unlike Alešek, who was robust, he was fragile. At three months old he had something that looked dangerously like pneumonia; fortunately he got over it. But he was prone to more infections, was pale and did not eat enough. Sometimes Alešek joined him for middle ear infections and then Dr Kejř came to the flat and pierced their ear drums.

To save

Pavlíček, Robert Jan stepped in again.

He rebuilt Vila for the second time, removing the top staircase from the first floor flat and moved Mářa's family there. It was great for everyone.

They moved in on the feast of St Nicholas of 1930. On the 16th of January 1931, Bety Bauerová started working for Mářa.

In the summer of 1930 and 1931, the family went on holiday to Kitzbühel in the Austrian part of Tyrol. The four-seater Tatra, now with the body crafted by Sodomka, took four adults and two children. The adults were Laďa, Mářa, Bábinka profesorová and a student Štěpánka who was employed to look after the children. She spoke German to them. Travelling by car did not agree with Pavlíček, he was often sick.

In Kitzbühel, the Vavruchs met Trude and Walter Honig who became their good friends. Mářa and Laďa visited the Honigs twice in Vienna and a few years later the Honigs, who were Jewish, escaped with their son Herhart to America.

Just like the Kořáns, Robert Jan, Marie and Vikin, Laďa liked mountains and they all knew the Alps well. Laďa enjoyed both walking and skiing there and it was good for his health.

His lungs were prone to bronchitis and all kinds of associated problems. He had one of those episodes when he went to Kitzbühel in 1930.

He got tired very quickly when walking, he perspired during the night and could not sleep. But the mountain air helped him, he recovered and was well when returning home.

Because of his health problems, Laďa avoided cold drinks. Instead there was always a big bottle of Vincentka on the table for everybody to use. At room temperature. This mineral water contains residual water from the Tertiary sea that rises to the surface in Luhačovice. It's an acquired taste.

Laďa tried to keep fit. Besides skiing, skating and walking [I don't remember seeing him running], he liked to play tennis and ride a bicycle. He showered in cold water.

His problem was sleep. He liked to switch off at 10, slept well but then he woke up early in the morning and could not fall asleep again. It was due to overwork, worries, tiredness and his weak nerves. Later in the morning he would sleep, but had to get up. It was good when he managed to take a quick nap after lunch.

In 1934, the whole family went to ski in Harrachov in

Krkonoše. Other favourites were Rokytnice and Špindlerův Mlýn. In February 1935, Laďa went on his own to Gerlosplatte in the Alps for just a few days of best skiing of his life. During Christmas of 1935, the whole family went to Zell am See in the Alps. The boys started to ski. For Easter in 1936 the family went to Štrbské Pleso in the High Tatras where the skiing was better than in Lomnica.

In summer that year, Alešek went to a boy scouts camp and Mářa, Pavlíček and Bábinka profesorová booked themselves into a resort in Český Šternberk, a few kilometres from the camp. There was wonderful swimming in the river Sázava there. Laďa did not care for swimming so he went to the Alps to ski at high altitudes in summer. He did not get there. Somebody stole his passport, tickets and all his money. He got off the train in Linz and asked the consulate for help. Mářa writes with a measure of glee that his stay in Český Šternberk was also pleasant for him.

After all, Laďa liked to spend time with

his sons.

Before the boys were born, Mářa and Laďa went to ski for just one day. There were two options. The easy one that Olu liked was going by train and bus to Janské Lázně in Krkonoše where a hotel was booked. In the morning by the cable car to Černá hora and skiing around big chalets until almost dark.

The coarse option was taken when it was not possible to leave on Saturday evening. A crack-of-dawn packed train to Liberec, then by a tram as far as it went, followed by walking up all the way to the top of Ještěd. Half way up, it was possible to have lunch. Skiing in the afternoon and the same way home, with soggy shoes and dead tired.

The Vavruch family in the 1920s and 1930s could afford long holidays abroad or anywhere in Czechoslovakia, but they did not waste money. They had their ways of economising, for example they never took the afternoon tea in the hotels.

A lot of money was spent on highly-qualified tutors who came to Vila.

It was languages (German, French, English or even Latin), also maths and primary school subjects for

Pavlíček when he missed a lot of school.

Pavlíček did not take it too seriously. For his lessons with Mr Kochánek, he was preparing by saying,

Kochi, Kochi, budu se mu smát! (Kochi, Kochi, I'll be laughing at him). The children had nicknames for all the tutors, the best was Ivan's 'Op' (short for ape) for Prof. František Prokop.

Laďa did not like how religious education was done at school, so the boys did not attend it and, instead, Pater PhDr Vilém Wilhum came to teach them in Vila. Eva Květová taught piano playing but that was probably free of charge. Laďa and Mářa were also educating themselves, it was English, French conversation for Laďa and an advanced French course for Mářa. Mářa was also getting singing lessons.

In the end, Laďa read in four languages. He recorded comments about books that he read, so we know that, in English, he read works by Will Durant, Plato, Aristoteles, Francis Bacon, Spinoza, Voltaire, Loche, Berkeley, Hume, Kant, Hegel, Schoppenhauer, Spencer, Nietsche, Bergson, Benedette Croce, Bertrand Russel, George Santayana, William James and John Dewey.

Influenced by Vikin's free spending habits, clothes for Mářa and Laďa were not bought in a shop, they were made to measure. On the other hand, as little as possible was spent on clothes for the children.

Duncanism

Vila with its garden and clean air was very good for Pavlíček but not good enough. Mountain air would be even better. He needed it to cure his bronchial glands.

So in March 1932 Mářa left, as she put it, for the unknown. Tatranská Lomnica was selected because there were no patients with acute tuberculosis there.

Feverish after a minor operation, Mářa travelled with the boys by sleeper train.

She knew only one name in Lomnica but soon she found something better and moved into the pension of MUDr František Bělín.

It was a long stay that included the summer holidays. (

See photo)

Dr Bělín with the help of Dr Hruška of Starý Smokovec got Pavlíček into a much better shape and during the following few years Pavlíček came there again for shorter stays.

Laďa arrived for Easter with a broken arm, he managed to break it when he was cranking a car engine in very cold weather.

To his surprise, he discovered that Dr Bělín had been his classmate in Prostějov.

He came again in June for the holidays.

Shortly before he travelled to Lomnica, Laďa made the most fateful discovery of his life. Just by chance.

He went to Vinohradské divadlo to A Midsummer Night's Dream performed by disciples of

Elizabeth Duncan's course that was running in Unitaria near Charles bridge.

Elizabeth ('Tanta' to her close friends) brought in her strongest team: the dance teacher Gertrud Drück, one of the followers of

Isadora Duncan before WWI, and the director of the group, pianist Max Merz.

As most of the disciples came from the families of luminaries, one can assume that the course was expensive.

Tanta, elder sister of Isadora, no longer danced herself, but was a tremendous dance teacher. She had the ability to get the most out of a dancer and to lead her student's imagination to the inner sensation of movement.

She danced in her youth. When Laďa and Mářa met her, she was permanently limping after a sledge accident in the Alps. She was also a quite unique character thus justifying Mářa's separate manuscript.

Tanta greeted Laďa, who called on her the next day after the theatre performance, as an old friend. She pulled out her teapot that she carried around the world and made him tea. She showed him photographs of Isadora, of some followers and of their seat at Kleßheim near Salzburg as well as some posters and some programmes of performances. Then she invited Laďa to observe a course session.

Laďa was taken, he was excited. He wrote to Mářa. He did not know that dance could be so natural, nothing artificial, nothing forced, but just natural movement of the body full of feeling and expressing the dancer's own soul.

Arriving in Lomnica, he invited a small group and, on a meadow above the town, he demonstrated what he learnt, encouraging his audience to accompany him by singing folk songs. He was full of ideas. He was 37 and he devoted himself to it for the rest of his life. It became his special way of expressing himself.

From then on, Laďa devoted a lot of time to dance. He thought about it, from the basics, how the human body moves, what makes it beautiful, how to express poetry and music with dance.

And he

practised. He also visited performances of a variety of dancers, local and international, of the latter he was very interested in Uday Shankar.

Later he developed a programme for himself. He worked out the choreography, polishing it and improving it. It comprised seven pieces that he played on a windup gramophone His master's voice [last seen in Västerås under Pavel's bed]:

Schubert -

Rosamunde (probably

Ballet Suite No. 2)

Dvořák - Walz (probably

Serenade for Strings in E Major, Op. 22, B. 52)

Liszt -

Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2

Beethoven -

Adagio Cantabile from

Sonata Pathétique No. 8

Mozart - probably

Minuet from Divertimento in D Major No. 17, K. 334

Handel - dances from

Alcina: probably

Gavotte and

Tamburino

Smetana -

Furiant from

Prodaná nevěsta

It was never performed in public.

Laďa tried to attract young men to become his followers and start dancing but none of them were prepared to dedicate enough time for that.

Tanta was invited to come to Prague by a group of personalities who knew about Duncanism and wanted to promote it.

The first was Augustin Očenášek who at Sokol in Žižkov tried to introduce free, spontaneous movements to children's exercises even before he knew about Duncanism.

There were two associate professors Gustav Vejšický and Jiří Václav Klíma,

and in particular

PhDr Emanuel Siblík who as Czechoslovak cultural attaché in Paris knew Isadora Duncan.

Siblík

was not new to these ideas.

Prof. MUDr Karel Weigner was a top-class anatomist who contributed widely to the theoretical aspects of Duncanism.

Because Duncanism in Prague at that time was not just dancing but also arguing about it. It was all very serious.

The only joke, allowed by some, was to call dancing 'duncání' [doontsahgnee].

We don't know if they left any records, anything in writing, anything that Laďa could build on.

Siblík, whose profession was aesthetics, brought artists like Karel Svolinský, Emanuel Frinta, Běla Vrbová and Prof. Antonín Landa.

This group met regularly and Laďa quickly became a part of it.

He was one of the instigators of

Společnost Elisabety Duncanové (sic) and a co-founder of

Škola pohybové výchovy Jarmily Jeřábkové.

After quite a long period when Jarmila used Unitaria, Laďa was instrumental in establishing 'Ateliér' on the top floor of the back wing of Palace Metro at Národní třída 28.

It was in 1938.

Ateliér made it possible for the Duncan method to thrive in Prague – more than anywhere else in the world.

When he was in Prague, Laďa went to Ateliér to exercise early in the morning.

There was also a more general professional institution,

Tanec, rytmika, gymnastika. In the end, it was organised by my mother and used our street address.

In 1929, the group sent then 17 years old Jarmila Jeřábková to Kleßheim because they recognised her innate ability to move most gracefully and express music in her dance.

She was extraordinary and she was herself a wonderful person. She travelled with Tanta to Paris and to Germany.

When she returned in 1932, she started teaching at various places, in Slaný and in Prague, and for a great variety of organisations. Until she got her own school.

My mother writes about Jarmila with admiration.

But she does not write much about Jarmila, only that Jarmila, often with a few other girls, joined the Vavruchs for holidays abroad, e.g. to Malinska in Croatia in 1938.

It looks as if Jarmila was in the late 30s and early 40s

part of our family.

In November 1939, the first night after Domeček was built, Mářa, Laďa and

Jarmila slept there. We just don't know who slept where.

Apparently both Laďa and Mářa were

happy with that.

Private life, part two

Another tragedy struck late in 1932. After returning from their holiday stay in Žďár nad Sázavou, Zdeněk started feeling sick.

He ignored it, it was just a cold, and continued to work very hard. When he went to the doctor, it was too late.

Inflamed sinuses infected the frontal sinuses in his forehead and he was losing eyesight. He was operated on but sepsis could not be stopped and he died on the 8th of December 1932. He was only 43.

It was a shock for the whole family, terrible for his mother Bábinka profesorová, Eliška and his children, Ivan, who was fourteen, and Alena, who was eight. The Kořáns, of course, showed full support which included ensuring that Eliška's standard of living would not be affected.

In the summer of 1933, Laďa, Mářa and Alešek (Pavlíček was in Lomnica with a

nanny) went to Kleßheim to the Duncan course.

It was great. Throughout, the unique Duncan atmosphere was maintained – there were not only dancing workshops but also an emphasis on fine arts led by a sculptor Fräulein Pompe, and the music appreciation programme presented by Max Merz. Evenings were spent inside in the big hall or outside, everybody singing.

The children’s programme was organised by Maria Ziemann, who later invited Alešek and Pavlíček to a children's masked ball in Prague where she taught German.

That year, the Duncans ended their stay at Kleßheim and the next year the course was in Kynžvart near Mariánské Lázně, while Gertrud and Max settled, for a while, in Rapallo, 25 km from Genoa.

Tanta travelled a lot and Mářa accompanied her a few times.

In 1934, Laďa attended the 7th Philosophical Congress that took place in Prague. He made detailed notes about the papers presented there, most of it in German.

In June the same year, the Czechoslovak Red Cross threw a garden party in the Royal Garden, hosted by Alice Masaryková, daughter of TGM and the chairlady of the organisation, and Hana Benešová, wife of Edvard Beneš.

The father of

Julinka Kučerová, one of the Květs' (and thus also the Vavruchs') closest friends, was

Josef Groh, the director of the Red Cross in Prague.

Laďa suggested to him that the Duncan girls could present a dance there. It was accepted, they danced to Dvořák's Polonaise and a few other pieces and it was beautiful.

During WWI, Josef Groh was the landlord of Masaryk's family that was left behind in Prague. They lived, free of charge, in Mickiewiczova ulice 13, halfway between Písecká brána and Bílek's villa.

In 1935, Laďa replaced his Tatra with a Chrysler. Judging by the

shape of it, he bought it second hand but we don't know the background. We know that the boys liked it because it had a strong engine, probably a straight 6 with a flat head.

So they went to Lomnica in that car for Easter and to Šumava for Pentecost. As they were driving along, they saw a sign inviting them to Hůrka and it became their favourite place for a few years. Mářa took the detour as her birthday present (the 9th of June). Czechs were in the minority in Hůrka but there were very nice people there, particularly the priest ThDr PhDr Ignác Březina. They went back there in the autumn without the children. The second last visit was in 1937 when the whole village, both the Czechs and the Germans, participated in the unveiling of a memorial of those fallen in WWI. This visit was memorable because Laďa was so happy, merry and keen to participate. [So it was not always like that.]

One year later, everything changed. The Germans started to show their resentment.

In nearby Železná Ruda, the German youngsters from the village marched in uniforms resembling those of the Hitlerjugend.

(See a

Czech article about German behaviour.)

When Hitler occupied Czechoslovakia, the innkeeper Herman Schmid and his son were arrested, they were Social Democrats. Their further fate is unknown. After the war, the Germans were chased out and the village became a part of a military base. The wooden church burned down, the buildings became targets. Only the chapel in the cemetery survived.

(

See photos at the bottom, including a list of some people known to be killed in Šumava when they tried to leave Czechoslovakia illegally)

(

and two street views in Google:

Kaple sv. Kříže with other photos, including a plaque of Ignác Březina and the foundations of the church. Also

a video in Czech)

Expelling the Germans was done brutally. And it was not done properly. Some people tried, many of them students. Alena Vavruchová went to Hartmanice in Šumava

to count hens and rabbits of Herr Opitz. Herr Opitz would have liked Alena to put in a good word for him so he could stay, but he was a Nazi so he had to go. Later, when Sudetenland was deserted, Alena went to Borová Lada

(panoramic view)

to harvest hay.

In 1936, Tanta moved to Munich. Laďa and Mářa went to visit her there and when she came to Prague, she was always a guest in Vila.

She also gave Laďa private lessons.

He wrote that he experienced it with his whole being and afterwards he felt lightness, joy and beauty that easily carried him over the difficulties of the daily life:

Po cvičných hodinách, které jsem celou svou bytostí prožil, jsem cítil lehkost, radost, krásu přenášející hravě přes obtíže denního života. And Jarmila was told by some girls who went to Ateliér that her dance lessons were giving them joyfulness with which to go through the haste, work and worries of the whole week.

Laďa thought about it: Did anybody explain it scientifically or philosophically? He was determined to find out. He tried hard, he went far and wide in his research.

He did not find much. Only much later he realised that it was psychologists who might be able to to throw some light on it.

However, the connection between the right kind of physical activity and the psyche could not be disputed. It was possible to teach that, it works.

Tanta and Jarmila knew how to do it. And Laďa could try to describe it.

[Am I right that in Laďa's time we did not even know that emotions are generated in the oldest part of the brain which we have in common with other animals?]

In August 1936, Jarmila organised a summer school in Velké Opatovice near Jevíčko in Moravia. It followed the example of Kleßheim but with local leaders, like Emanuel Frinta who talked about fine arts and taught the participants to draw. Two new things were filming and picking up mushrooms that were in abundance in the milieu. Frinta was an expert in that field as well. The Vavruch family was there and enjoyed it.

Other than that, 1936 was bad for Laďa because he had a serious bronchitis that was dragging on.

The next year Jarmila won the first prize, the gold medal, at a congress in Paris dealing with physical activity education. It was a great honour.

Protektorat

(

YouTube, 14';

YouTube, 10';

YouTube in Czech, 1 h)

[In 29 pages, Mářa describes the situation in Vila and in Cerekvice from the very beginning: the household, factory, personnel and then she carries on with the horrid times from the betrayal and occupation of Czechoslovakia to the longed-for liberation by the Red Army.

Most of that has no direct bearing on Laďa's story.]

During tough times, Laďa stood firm, his unshakable optimism in place. He tried to keep the family life as normal as possible and help where it was needed.

In June 1938, the family went to the Beskids with Laďa's classmate and best friend, MUDr Ladislav Roháček (1896-1976).

[Mářa once told me that Roháček was the only other man she would ever marry.]

During mobilisation, both Laďa and Vikin were called up,

Laďa to České Budějovice to command a field hospital and Vikin to Slovakia. Soon they returned home. For Laďa, it was a holiday. He met new friends and returned recharged, full of energy.

For Vikin, it was an ego trip. He was very popular in his unit and when his train stopped in Choceň, he exchanged cheerful greetings from the top of an open wagon with the local railwaymen. They knew him well because he had been changing trains there so many times. This time, he could not change to the local train in the direction Vysoké Mýto - Cerekvice - Litomyšl because he had to stay with the unit for another day or two. In the meantime, Vikin's classmate Jaroslav Kose stopped with his unit in Cerekvice. His horses and wagons were a great attraction there.

After the

Munich Agreement, people were devastated, some were despairing and some were affected in various ways.

Robert Jan had a facial nerve palsy, it was quite serious. Alena's dachshund Lesan could not stand watching all that and died.

Laďa spent most of his time in Prague helping central institutions to reorganise the industry to suit changed conditions.

Czechs engage in non-ending discussions about whether the republic should have fought Hitler.

People who say yes (

in Czech), maintain that giving up without a fight crippled the nation's character. But nobody assumes that we could have won and there are so many arguments against fighting.

Beneš (

criticized in Czech by Pithart,

the whole video) correctly predicted that the war was inevitable and we could fight when there was a chance of success.

And we did. Czechoslovaks were among the best pilots in the Battle of Britain, more were in the British army and Svoboda's army had 16 000 soldiers, several of them Volhynian Czechs.

Near the end, Slovaks rebelled on a big scale and there was an uprising in Prague. There were many partisans. 25 000 Czechoslovak soldiers died in the war.

On the 27th of November 1938, Vikin married

Jari. He had divorced Olu in 1936. According to Slávina, Olu went through life with head in the clouds while Vikin was down to earth practical person.

Vikin and Jari moved into a modern flat, got specially designed furniture, made it nice...and lost it. In 1939, they were kicked out to make space for some German officers. Jari then turned her creative energy to improving the house in Cerekvice.

In 1939, the Nazis simplified the banking sector and the Länderbank was merged with a German bank. Fortunately, as the term of the Kořán’s loan was expiring, it was possible to transfer it to Živnobanka. Laďa was the chief negotiator. It was harrowing. Once, at the bank's law firm, with both Vikin and Laďa present, drafting the contract took a solid 16 hours. Later, Robert Jan also involved himself and was pleased how banks now valued his firm as a customer. He was recovering from a mishap: returning to Cerekvice at night, in a dark pantry, he took a bottle and started to drink. Unfortunately, it was not mineral water but paraffin for lamps. They had to pump out his stomach. The recovery was lengthy, Robert Jan was again seriously ill.

Laďa was appointed the CEO and a 'forced guardian' (vnucený správce) of sugar factories taken from Mr Bondy who was Jewish. Bondy was a good man and both Robert Jan and Vikin worked for him as consultants. Laďa did not ask for that assignment but JUDr Vlastimil Šádek (1893-1961), Minister of Industry, Trade and Small Businesses, and Laďa's friend from Prostějov, clearly thought that the appointment might shield Laďa, a Social Democrat, from prosecution by the Nazis.

Laďa's SocDem party was, of course, banned, but Nazis were well informed and arrested many prominent Czechs, some of which – in the first phase about 500, in total more than 15 000 – were sentenced and executed within three days. In Brno, local German inhabitants enjoyed observing public executions of Czech patriots. Altogether 63 000 non-Jew civilians and 277 000 Jews died.

The forced guardianship was too much for Laďa's weak nerves. Fortunately, in the management team there was Herr Holy, a malicious Nazi and a real idiot, who opposed the appointment. After some high-level struggles, the appointment was cancelled and Laďa was relieved.

Šádek also enrolled Laďa in the only party allowed in Protektorat, 'Národní souručenství', formally led by Staatspräsident Emil Hácha. No other parties were allowed, not even fascist parties. Thus the full scale of characters was in the party, some of whom were prosecuted after the liberation. Laďa did not show any activity in the party.

On the 17th of November 1939,

Ivan, son of Zdeněk and Eliška, went to the university for one of his final exams.

When he arrived, the university was closed, guarded by German soldiers.

Ivan did not know that that day 1200 students were arrested, beaten up and sent to concentration camps, all girls to

Ravensbrück.

Nine students were

shot. Hácha demanded release of the students. He tried very hard but not in all cases successfully.

Czech universities were permanently closed and there was danger that Ivan would be sent to forced labour in the Reich.